Environmental Machine Drawing | Simon Kirby

I had just turned 50 at the height of the first wave of the pandemic last year when I decided to buy myself a robot...

Prior to the pandemic, my artistic world had been one of collaboration, grounded strongly in a sense of place. My last two projects were site-specific sound works: Sing the Gloaming, an exploration of language evolution installed in a Scottish forest; and Concrete Antenna, an installation in the landmark tower of the Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop that reacted to the turning of the local tide. The pandemic made this artistic exploration of physical space seem impossible. Our horizons shrank to the walls of our homes, collaboration only possible digitally through the increasingly overloaded channel of the laptop screen.

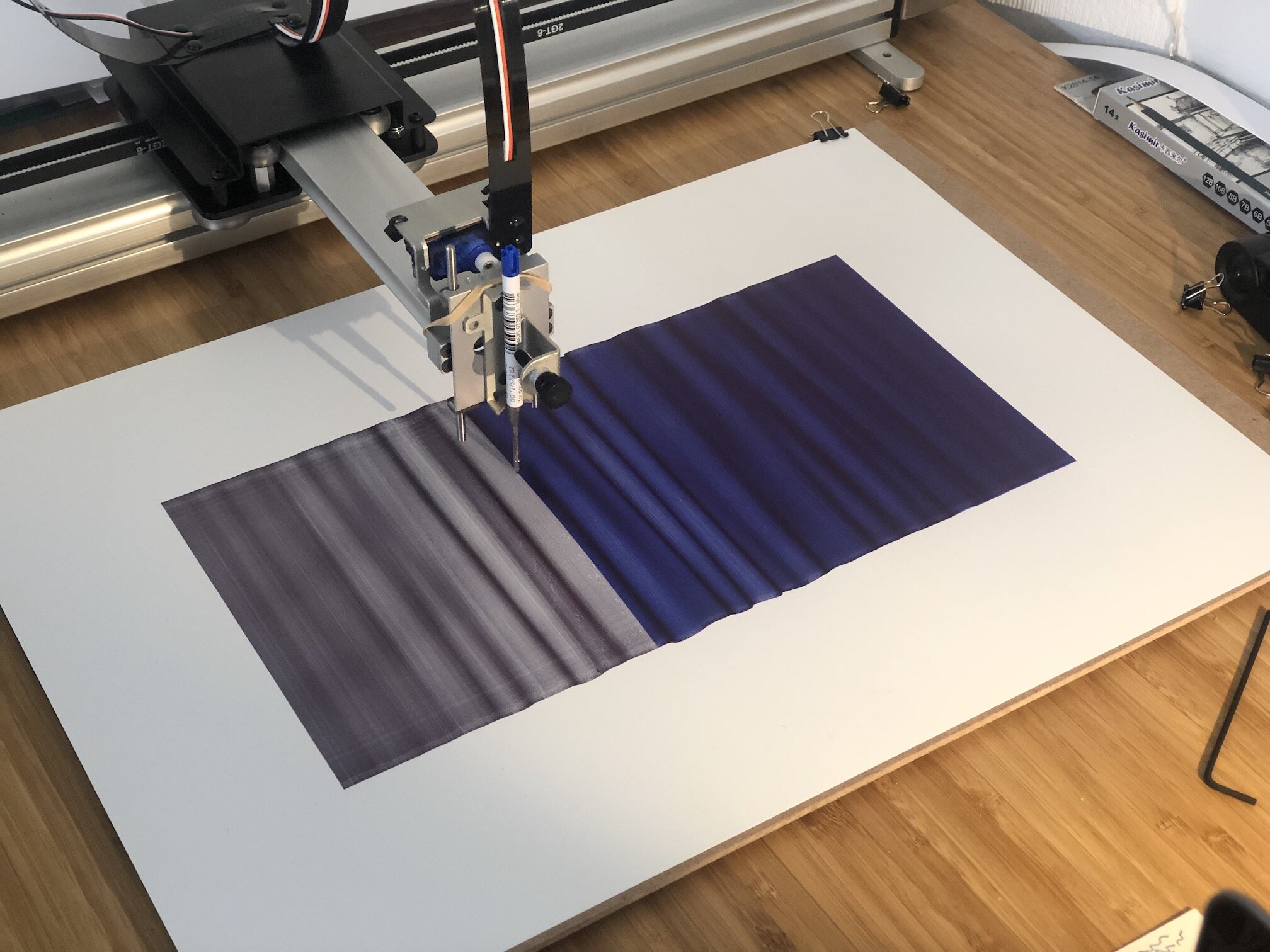

The Axidraw plotting robot at work | Simon often uses standard office ballpoint pen refills with the robot – elastic bands control the degree of pressure on the paper

I didn’t have much of a plan when I placed my order for the robot, beyond a desire to do something that broke out of that laptop screen and into the real physical world. It is a relatively simple device: a pen-plotter that can hold a drawing implement and move it rapidly and precisely wherever my computer tells it to go. But there is something magical about what it does. Unlike a printer, what you get with a plotter is never quite what you see on the screen. Using it means learning about mark making in new ways, exploring how pen, ink, and paper interact; how the way a pen accelerates and decelerates on a page change the flow of the line; how adjusting downward pressure (using a rubber band, as it happens) changes intensity. These things are instinctive to the human artist, but need to be taught to a robot. The reward is being able to produce an uncanny effect: a drawing that is clearly made using pen and ink, but with many thousands of lines laid down in impossible sub-millimetre precision.

The robot can also hold fountain pens at an angle, allowing the use of hand-mixed document ink

The pen plotter mediates between the physical analog world and the world of digital algorithms and mathematical structures. Rather than determining exactly where lines are drawn, I write code that generates the movements of the plotter arm. This approach requires a lengthy period of experimentation. I play with simple interacting processes in the computer and see what the plotter does. What emerges feels more like a collaboration between me and the machine than anything else.

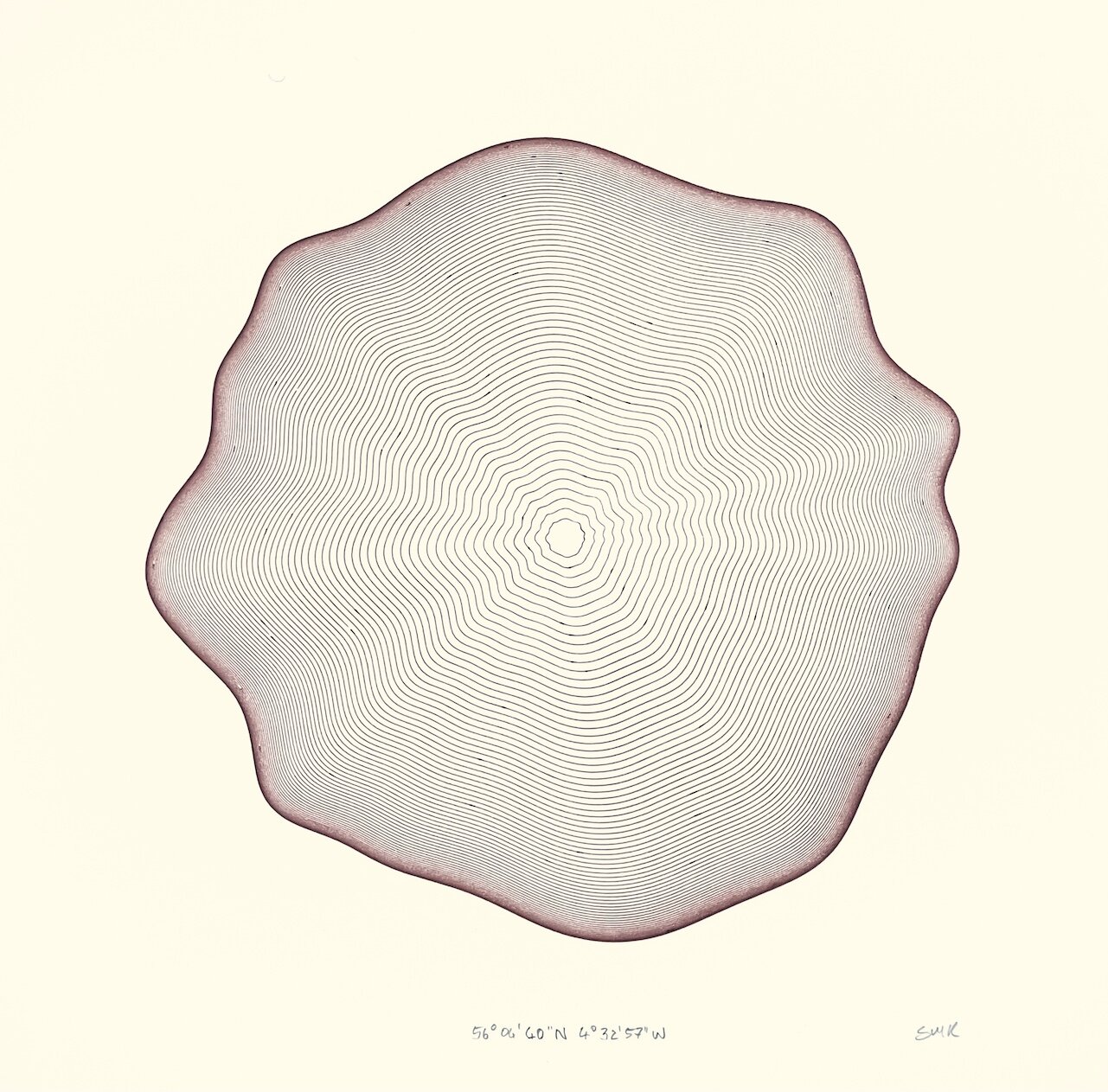

Tree Rings

Many of the algorithms I use need to be “seeded” by some data that distort the otherwise perfect lines the machine produces. Rather than these seeds being arbitrary, I wondered whether they could relate in some way to important places on Earth. In lockdown it felt essential to find a way of honouring places we would not be able to see. For the Tree Rings series, I create drawings seeded by latitude and longitude coordinates that people send me via my website. Each one-off drawing is unique to that point on the Earth’s surface, acting in some way like a fingerprint of that location. Although the relationship between the tree ring patterns and the location provided is essentially arbitrary, nevertheless there is something powerful about knowing this particular pattern of rings can only be created by the particular latitude and longitude I input into the algorithm.

Tree Rings for Inchcailloch | Hand-mixed fountain pen ink on ivory board | 30cm x 30cm

Detail from Tree Rings

I have been moved by the stories of the places that people choose for their personalised drawing, ranging from birth places and locations of marriage proposals, to the site where ashes were scattered. As the plotter prepares the drawing, I look up the location on google earth, and feel a connection in some way to those strangers who are venerating a location that they are not currently allowed to visit.

“When I look across these drawings, created over the course of half a pandemic year, I am struck by how they reflect an urgent need to reconnect to landscapes. Places have power. ”

Portsoy

The data that seeds the Tree Rings drawings is a purely numerical object, merely the coordinates of a location. For my next series of drawings I wanted to capture the essence of a place more directly. I wondered if I could somehow ground the image in something of the landscape that is non-visual. During the lull between the two peaks of the pandemic, some travel became possible, and I visited the fishing village of Portsoy on the Moray coast in Scotland. There, I recorded the sound of waves on the harbour wall. These digitised field recordings became the data for my drawing Portsoy.

Portsoy | 8 layers of blue and black ballpoint pen on yupo paper | 30cm x 42cm

Detail from Portsoy

The sea at Portsoy harbour

Whereas my previous drawings used fountain pen, for Portsoy I was interested in experimenting with other types of pen. I was intrigued to see what the effect would be of using that most familiar and humble of writing implements, the office ballpoint. The oil-based ink in ballpoint pens in combination with waterproof paper allows me to create drawings made up of tens of thousands of lines, which would otherwise destroy wood-based paper with water-based ink. Portsoy uses black and blue ballpoint refills. With 8 layers and two days of drawing time, the result is both recognisably a ballpoint pen drawing, but also unfamiliar in the intensity of its colour.

Camas Thairbearnais

Camas Thairbearnais extends the field recording technique I developed for Portsoy by also using maps of the area where those recordings were taken. The top line of the drawing traces part of the coast on the north shore of the Hebridean Island of Canna. This line is gradually eroded and distorted down the page by sound I recorded of waves moving the pebbles on that same shoreline last year.

Camas Thairbearnais | Sepia ballpoint pen on yupo paper | 30cm x 42cm

Cliffs on the Isle of Canna

Detail from Camas Thairbearnais

For Camas Thairbearnais, I experimented with a range of ballpoint pens, and settled on a Fisher Space Pen (famously used by the Apollo astronauts). The ink here is less viscous to allow for a pressurised refill and smoother flow. The result is a very controllable degree of gradation in the drawing. Most of the thousand or so lines in this drawing are actually plotted in the first few millimetres at the top of the picture.

Jordan Burn

By December last year, we were heading back into lockdown and it felt like our horizons were shrinking once again. My son had been taking long walks locally every day of the pandemic and as a result had explored every inch of the local neighbourhood. On Christmas Day, he took me to the grounds of the local hospital where he’d discovered a tiny stream that emerged from underground briefly there before disappearing again. He explained that this was the Jordan Burn, a culverted river that used to run along the south boundary of Edinburgh but was now almost entirely lost under the streets of the city.

Roy Military Survey map of south Edinburgh 1747-1755, showing the original course of the Jordan Burn

I took a recording of the stream that day and set about trying to find old maps showing its historic course. The most recent of my drawings, Jordan Burn, is the result. The river runs through the middle of the page, which is oriented with east at the top. The lines to either side are progressively distorted by the sound I recorded that day on the walk with my son.

Jordan Burn | Sepia ballpoint pen on yupo paper | 30cm x 42cm

Detail from Jordan Burn

When I look across these drawings, created over the course of half a pandemic year, I am struck by how they reflect an urgent need to reconnect to landscapes. Places have power. They resonate with us (or we with them) for reasons that are somehow both personal and universal. The lockdowns of this last year, however necessary, have been emotionally damaging in part because they have kept us from being in the places that nourish us. Perhaps a role for environmental art now is to recognise this hurt, and be part of the healing.

Simon is Professor of Language Evolution at the University of Edinburgh and elected Fellow of the British Academy, Royal Society of Edinburgh, Cognitive Science Society, and a member of the Academy of Europe. He works in parallel on scientific and artistic investigations of cultural evolution and the origins of human uniqueness, particularly the evolution of language. He founded the Centre for Language Evolution, which has pioneered techniques for growing languages in the experiment lab and exploring language evolution using computer simulations. His artistic work includes Cybraphon, which won a BAFTA in 2009 and is now part of the permanent collection of the National Museum of Scotland.

All images & text above © Simon Kirby | Produced for A La Luz, 2021 | Please do not re-publish any of the above without prior written consent