Culture Underwater

Invasion of the Inside

by the Outside

Featuring in Antony Gormley’s stunning Royal Academy retrospective exhibition is Host – a gallery room flooded with seawater. What Gormley calls “invasion of the inside by the outside”. Beneath the water, the artist has sealed the floor and skirting with clay. At the far end of the room we see a round-arched doorway rising above its reflection.

Host 2019 | Antony Gormly | Royal Academy, London

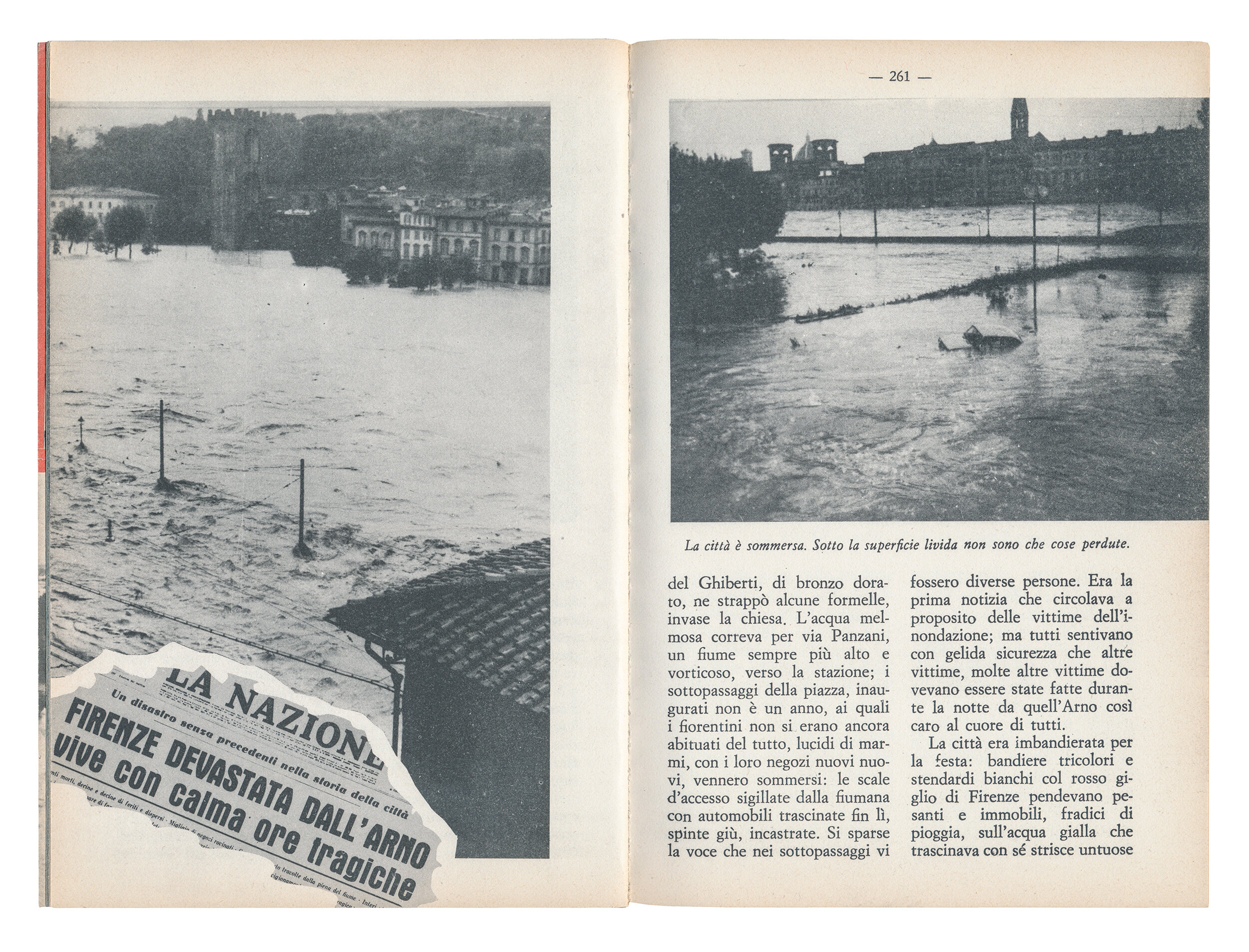

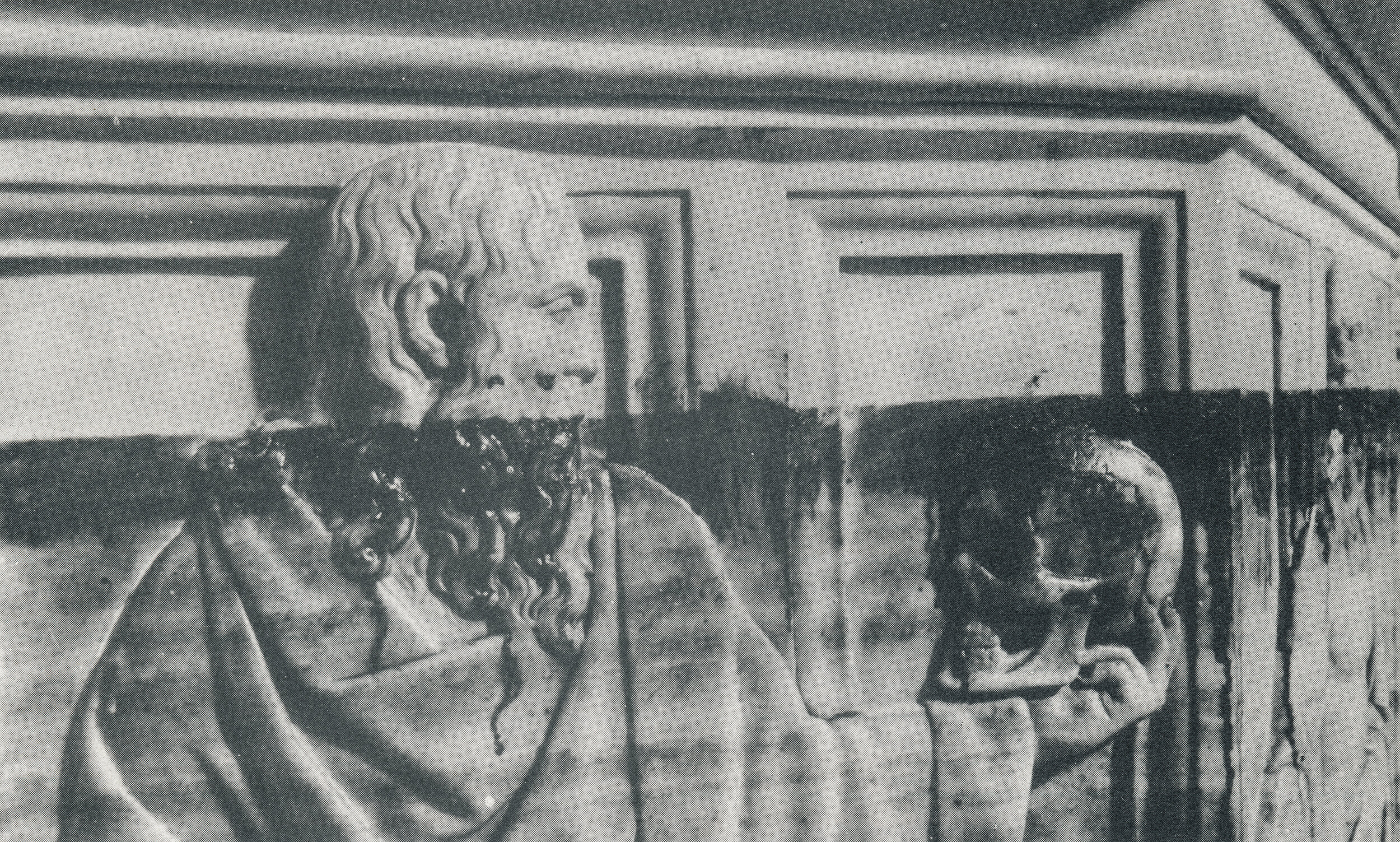

4.11.66 | Author unknown | Archive newspaper cutting

The first images that come to mind are of Florence or Venice: of elegant doorways rising from floodwaters in scenes of (ever increasing) acqua alta; or archival images of Florence’s devastating 1966 flood. Coincidentally, the anniversary of Florence’s flood is today.

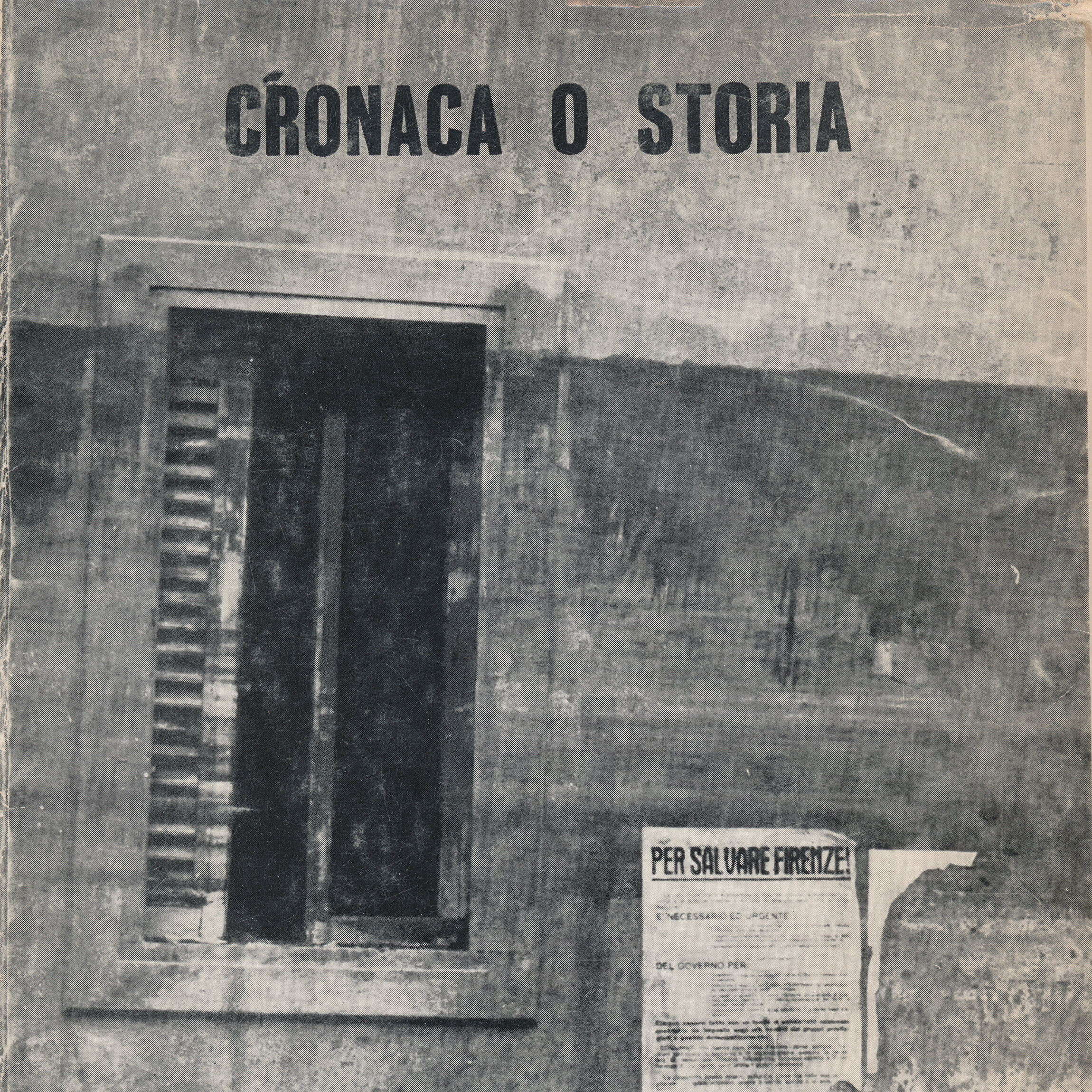

The Florence flood of 1966

In November 1966, Florence (Italy) experienced one of the worst floods in its history. The legacy of that flood lives on in the city today, yet, little has been done to safeguard against a similar event in the future. In just a single night, the birthplace of the Renaissance was reduced to a sea of mud. Flood-water engulfed some of the world’s most famous buildings, sights and works of art; claiming over 100 lives.

We ought to read Florence’s great flood as a cautionary tale for our time of climate crisis. Our Earth’s cultural landmarks are no less susceptible to forces of nature than anywhere else: as Gormley’s flooded Royal Academy suggests.

Background

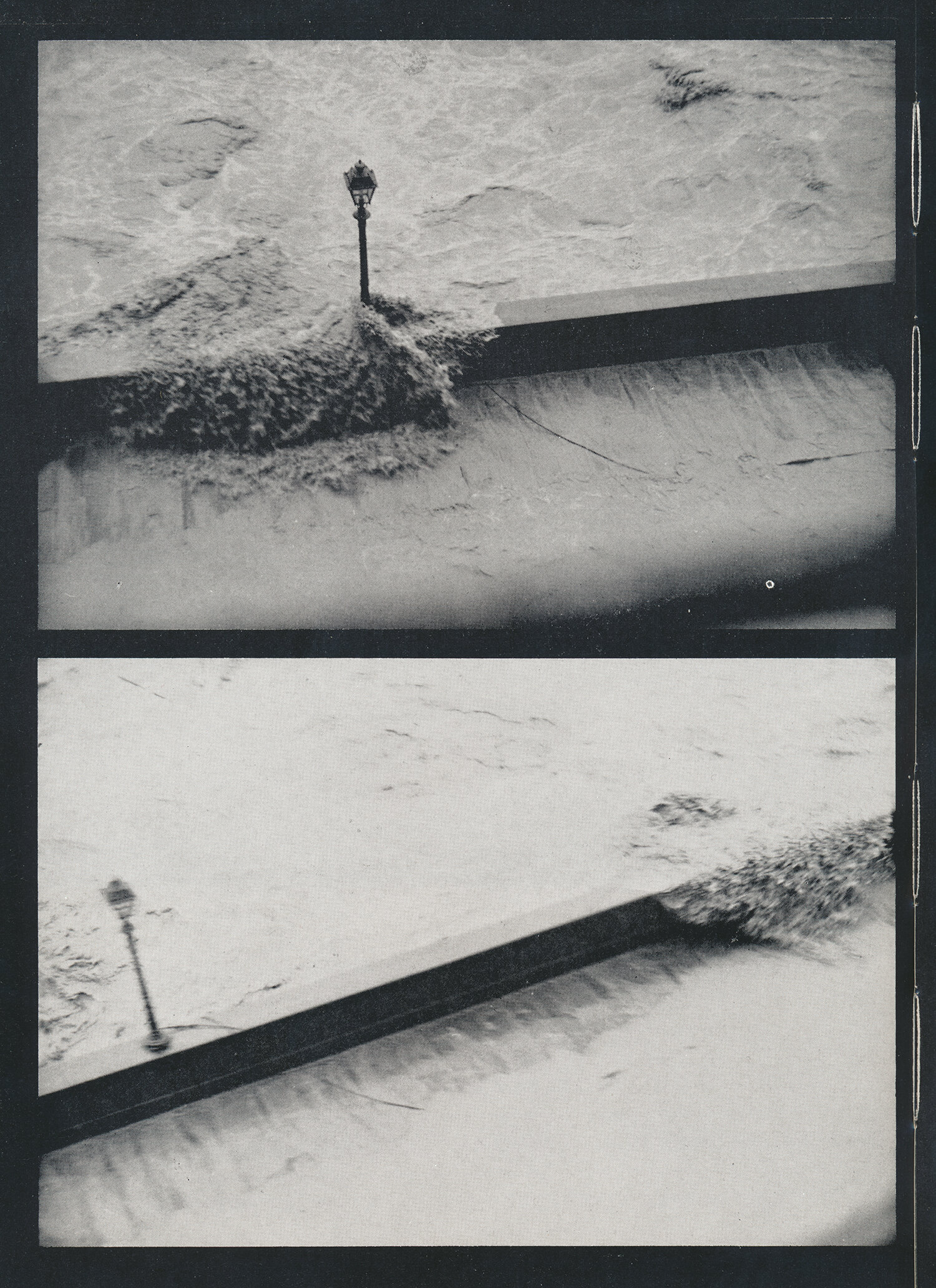

After a prolonged period of intense rain during the first days of November 1966 – fifty-three years ago today – two dams burst upstream of Florence. During the early hours of 4th November an enormous weight of water was propelled at great speed towards the medieval city.

The Arno river quickly burst its banks, filling every nook and crevice. Mud, clay, oil, fuel… contaminated water spread and rose – to 22 feet in the Santa Croce area – covering almost 7000 acres. By the evening of the very same day the waters began to recede, leaving behind some 600,000 tons of mud and debris. A ton of mud for each inhabitant. Traces of the flood still exist in the city today.

Florence exists not only for those that live there, holiday there & study there; but also in the collective memory & imagination. Florence is a – if not the – mecca of the art world.

People from around the world came to Florence’s aid in the aftermath of the inundation. So-called mud angels travelled on their own steam to help clean and salvage; others sent much-needed funds, tools and supplies.

Historically, Florence has suffered a major flood once a century. But as documented in the press ‘the situation has actually got worse’, according to Raffaello Nardi, who heads up a special commission responsible for safeguarding the Arno river basin. This risk prompts concern, in part, because of the importance of this city: what it means to the world of art and culture. The irreplaceable items, objects, artefacts and architectural features its galleries, museums, churches and even its basements contain. Not to mention the intangible: the knowledge – thanks to the rich catalogue of those that have come before – that Florence is a cornerstone of the art world.

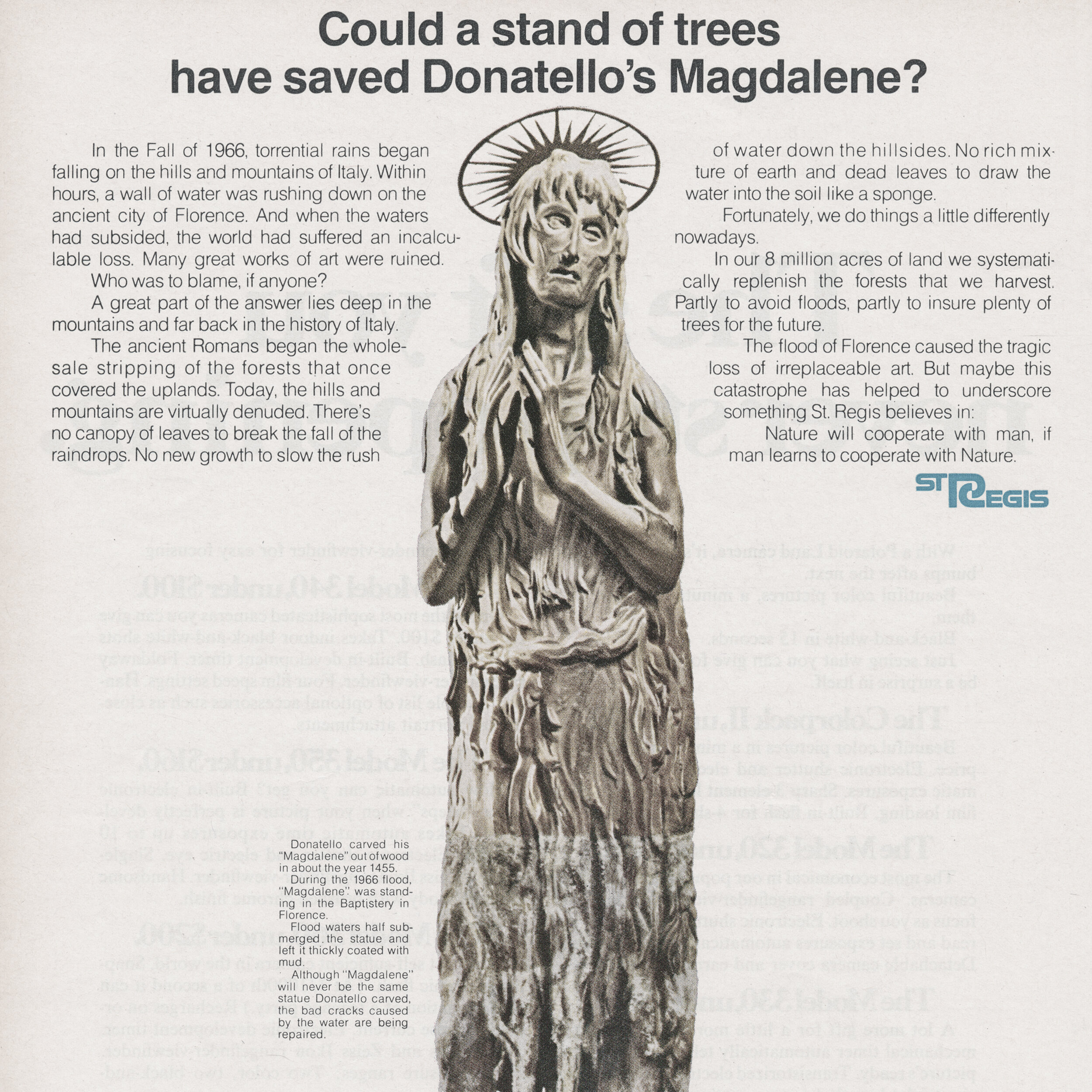

Cimabue’s cross lost over seventy-percent of its paint. Donatello’s Penitent Mary Magdalene was stained with thick brown oil. Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise lost half of their golden panels. Twenty-seven thousand square feet of frescoes in Florence’s central churches and museums were almost completely destroyed. Below, Taddeo Gaddi’s The Last Supper was heavily damaged, with some parts of the painting completely erased by flood-water. Hundreds of items are still under restoration today.

An original wire-photo from November 25th 1966: restorers cleaning Gaddi’s The Last Supper (1334–1366)

“During my first stay in Florence in the 1980s I learnt the phrase ‘chiuso per restauro’. Many churches, palazzi and works of art were inaccessible to visitors due to flood damage and the process of cleaning, repairing and conserving, which is still underway.

Now I live in Florence and realise that the 1966 flood is not just an historic event, commemorated by the water level markers around the city. Florence has suffered serious floods about every hundred years over the last seven centuries and every November, as the river runs faster than the traffic along the banks, Florentines old and new observe it nervously.”

The Flood of 1966 Leaves Florence a Legacy of Work and Fear | The New York Times (30.12.66)

What if?

As climate change advances and extreme weather events grow more common, we might ask what if this happens here again? This anxiety raises its head every year now in Florence. Most notably, during severe and prolonged rain in late January 2014, and again in November 2016. On those occasions the river was only centimetres from bursting its banks.

If we shift our gaze north-eastward, to Venice, our fear of losing precious pieces of our Earth’s cultural catalogue swells, as episodes of acqua alta (high water) become higher and more frequent. Since 1872, Venice has endured twenty episodes of extremely high water; with eleven of those occuring since 2000. We’ll go into more depth on this topic in a future post.

Last year the Louvre museum in Paris (which stores a quarter of its collection underground near the Seine river) was on high alert, after the previous year rooms housing Arts of Islam and From the Mediterranean Orient to Roman Times were flooded, and a set of works by Nicolas Poussin and Jean-François de Troy damaged.

The Louvre wasn’t the only Parisian cultural institution to take on water that year: the National Library of France suffered damages to its collection too; and the Musée Girodet, 80 miles south of Paris, suffered a “cultural catastrophe”.

Looking back to 2012, in New York the Tanja Grunert gallery, David Zwirner gallery and Zach Feuer gallery were among those inundated as a result of Hurricane Sandy, damaging works on show as well as those in storage.

It’s no longer a case of what if. It’s a question of when. We know now that so-called “hundred year” weather events are becoming so common that the metric is useless as a baseline for an extreme event. So, in tandem with reducing our environmental impact (and limiting our production of the greenhouse gasses that lead to irregular weather patterns) we must also safeguard.

While this article touches upon water related events, other extreme scenarios – such as wildfires – should also be considered. The Vice article Museums Are Trying to Fireproof Themselves in the Age of Climate Change is worth reading.

“Leonardo da Vinci, an apprentice in Verrocchio’s Florentine studio wrote, ‘L’acqua che tocchi dei fiumi e l’ultima di quella che andò e la prima di quella che viene. Così il tempo presente’. The water you touch in a river is the last of that which has passed, and the first of that which is coming. Thus it is the time present.

The Arno still runs, grey and forceful in winter rains that seem to grow more heavy with each passing year. While we can only hold our fingers in the teeming flow, forgetful of the past, eyes averted from the future. Anxious to convince ourselves the moment is all that matters, and that is ours alone.”

Banner flood-map + archival images comes from David Cass' collection of 1966 Florence flood ephemera | Image of 'Host' (Antony Gormley) taken by David Cass in the Royal Academy, London, November 2019